From Issue 1/76

Frost and Flight

When we say that we hate to tell this story, we really mean it. It's a story we've told you before but still needs retelling.

After takeoff the aircraft remained in a steep nose-high attitude. stalled, and dived into the ground. Witnesses heard the engine run erratically and it was not producing power at impact. However. more slgnificantly the aircraft was noticed minutes after the accident to be covered with a heavy layer of frost.

Medical evidence established that the pilot had experienced stress for several minutes before the impact, probably due to the feeling of doubt about his aircraft. And well he should have — the aircraft had been on the river overnight where it had accumulated a heavy layer of hoarfrost on its white wings. Further. a significant amount of ice and water was found in the fuel system. With the daily temperatures varying above and below freezing, condensation was inevitable in the half-filled tanks. The below-freezing temperatures at the time also added to risk of ice accumulation on the tailplane during takeoff.

He may have discounted the significance of the hoarfrost on his wings — if he had noticed it. In any case. it would have been an awkward job to remove it, with his high-wing aircraft sitting out on the water. But the fact remains that a wing will lose lift when the air rushing over the upper surface does not adhere firmly to its curvature. And nothing will unglue air more readily than the irregular surface created by hoarfrast or snow crust. Every year there's evidence that pilots choose to flirt with this lethal hazard.

Originally Published: ASL 1/1998

Original Article: From Issue 1/76 - Frost and Flight

From Issue 6/75

There's a school of thought which goes "you can't avoid having accidents", and we must admit that statistical evidence seems to be on their side. But a close look at accidents reveals that few, if any, ever needed to have taken place.

It's our firm opinion that assuming the inevitability of accidents saps the positive thinking of those who are in the best position to prevent them. Persons involved in accidents sometimes reveal a startling lack of appreciation for this fact. You'll hear "Some kinds of flying are dangerous; you only have to look at the accident record to see that"!

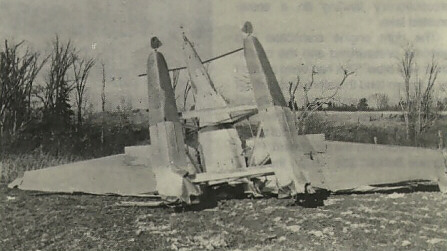

Take the pilot who lands a small ski-equipped cargo plane at a remote frozen lake. On landing he discovers that the surface is quite slushy and that he has picked up a fair amount of the stuff during the landing roll. He unloads his cargo, kicks off the accumulation around the skis and sets out for the takeoff. On his first attempt he gets nowhere so he decides to use the landing tracks. This time, things go a little better but acceleration is still poor. With only 250-300 yards of lake remaining at 40 mph "I elected to carry on and obtain 50 mph and rotate...". Inasmuch as there was a shoreline and trees at the end of the lake, that attitude took some self-control! The aircraft became airborne for a short distance but was so close to the stall that the aircraft wouldn't accelerate. The inevitable happened and the aircraft crash-landed into trees.

It was the pilot's contention that "I honestly don't know how this could have been avoided in this situation...". And he's right. The problem is that the pilot meant by "situation" the compelling urge to make good a takeoff run which obviously wasn't going well, and indeed, to attempt a takeoff in conditions like that in the first place. Certainly, there was pressure to get the aircraft out, but as it happened it stayed there for quite a while longer.

Originally Published: ASL 1/1998

Original Article: From Issue 6/75

From Issue 3/75

"Runway Lights in Sight..."

Last year 97 people were killed when a 707 entered a particularly steep rate of descent in the last 20 seconds of an instrument approach. As the runway became visible the first officer called "you're a little high", so the captain increased his rate of descent from 690 fpm to 1470 fpm. This excessive descent continued until the aircraft crashed.

Why? The captain had relied primarily on visual clues. The heavy rain on the windshield may have caused the runway lights to appear larger, thereby convincing the pilot he was cioser to the runway than he reallv was.

"Runway lights in sight..." is a reassuring call from the first officer but it means you're entering a critical phase of flight. That transition from instruments to the visual part of the landing requires more than just a casual check of the flight instruments. Your instrument scan should continue, adding to it visual clues (such as VASI) as they appear. This way, during transition you'll detect any deviations from the glidepath and desired rate of descent.

Having some visual clues may tempt you to abandon your instrument scan early but rain on the windshield changes the perception of distance on the approach. It can make lights appear larger which may convince you the runway is closer than it really is. With this iilusion it's easy to convince yourself to increase the rate of descent or descend prematurely. Or rain may cause runway lights to appear less intense by diffusing their glow. This would probably lead you to think that the lights are farther away than they actually are.

Don't fall into the visual trap. Maintain a good scan of your flight instruments as you transition from instrument phase to the visual approach and landing.

The Mirror Effect

Have you ever looked into a wall-to-wall mirror and wondered exactly where the surface was? Hard to tell, isn't it? It's the same thing when taking off or landing on glassy water.

Ask any experienced float pilot - glassy water operations are tricky and you need to be extra alert. Here's an example. After refuelling on shore, a chopper pilot moved to a hover over a glassy lake surface. As he began h is transition to forward flight the skids struck the water surface causing the chopper to tumble into the water. Fortunately the crevv escaped uninjured as the chopper was sinking.

The pilot said he had never been instructed on the hazards associated with glassy water operations. Have you? There is more information on this subject in Part 4 of the Flight Information Manual (FIM).

Originally Published: ASL 1/1998

Original Article: From Issue 3/75 - "Runway Lights in Sight..."; The Mirror Effect

To the Letter

Re: Struck by Lightning

Dear Mr. Schonberg,

As an interested and appreciative reader of the Aviation Safety Letter, and a professional pilot for the past 12 years, I was somewhat taken aback by the tone of the article on lightning strikes in Issue 3/97. The article insinuates that many highly trained and experienced airline crew members flew aircraft near a lightning storm merely to meet a schedule. The article also suggests that the on-board weather radar would have indicated this hazard, and that the crews either didn't use the radar or didn't care about the returns. I feel that both of these comments are inaccurate at best.

As you know, weather radar indicates returns from precipitation and is consequently very useful in avoiding turbulence, windshear and hail, but gives a pilot no indication of the electrical activity in a storm cell. Recent research suggests that many lightning strikes occur when the aircraft is abeam a storm cell, rather than under or in a cell, and that they can occur at distances up to 20 NM from the edge of a storm cell. In addition, the lightning-strike potential around a storm cell is highly variable and topography-dependent; an area that is safe at one point can quickly become unsafe, and vice versa.

While I am not saying that, with hindsight, the situation could not have been better managed, I feel that it is somewhat unfair to be so quick to judge. If all aircraft avoided thunderstorms by 20 NM at all times, most western Canadian airports would be closed every afternoon in the summer months! Conventional thought and practices seem to indicate that pilots can safely circumnavigate such storms using many sources of information. That is using weather radar, stormscopes (if the aircraft is so equipped), air traffic control, and pilot weather reports, and merely by looking out the front windshield. Thus, lightning strikes are a fairly rare occurrence and, when they do occur, the design of the aircraft does what it is supposed to do and damage is usually minimal. In light of the above, to suggest that several dozen professional pilots jeopardized their passengers' safety to make a schedule is somewhat rash.

Thank you once again for the Aviation Safety Letter. I find it to be a truly useful and educational resource that is very easily understood.

Kevin Maher

Vancouver, British Columbia

More Lightning

The article states that "The lightning could easily have fried the aircraft's electronics...."

Transport category aircraft certified to the Federal Aviation Regulations in the United States, Joint Aviation Requirements in Europe, or Canadian Aviation Regulations in Canada have to meet stringent airworthiness standards for protection against the effects of lightning strikes. Two types of effects have to be considered:

- direct effects: The aircraft must be shown to be able to withstand a direct lightning strike and not suffer structural or significant surface damage, nor shall any fuel in tanks, lines, and so on, be ignited by the strike; and

- indirect effects: The aircraft avionics and electrical systems, including electronic controls for systems such as landing gear, flight controls, and fuel management, must be able to withstand electrical impulses induced in the aircraft wiring as a result of the electromagnetic field created by a lightning strike.

As you can see from the above, there should be no risk of the electronics being fried. The aircraft may suffer minor surface damage from the lightning-strike attachment or discharge points, and the carrier should conduct a post-strike inspection of the exterior surface to determine the extent of any damage.

A few years ago, I was in a Canadian B-737 that was struck by lightning on approach to Vancouver International Airport. After disembarking, I stood by the window at the gate and was pleased to see a mechanic walking around the aircraft, looking carefully at the radome and rear lower fuselage, including antennas. Obviously, the flight crew had reported the strike to the ground crew.

John Carr

Principal Engineer

Avionics and Electrical Systems Engineering

Aircraft Certification Branch

Transport Canada

Originally Published: ASL 4/1997

Original Article: To the Letter - Re: Struck by Lightning