Beechcraft Bonanza V35B & Piper PA-28 - Mid Air Collision

The Beechcraft V35B Bonanza was in a shallow climb, heading southbound, in the vicinity of Warrenton, Virginia. The aircraft was operated under visual flight rules with the pilot under the supervision of an onboard instructor. The Piper PA-28 was in level flight, also under visual flight rules, and was heading in a southeasterly direction. The aircraft collided approximately 1800 feet above sea level. The Beechcraft broke up in flight, and the pilot and flight instructor were fatally injured. There was a post-impact fire at the Beechcraft accident site. The pilot of the Piper, who was the sole occupant of the aircraft, conducted a forced landing in a pasture, approximately 6 nautical miles south of the Warrenton-Fauquier Airport. The pilot sustained minor injuries.

The Piper was registered to a Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) employee, and the Beechcraft was registered to a National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) employee. Given the unique circumstances surrounding the ownership and operation of the accident aircraft, the United States government requested the Canadian Transportation Safety Board to investigate as an unbiased investigative authority.

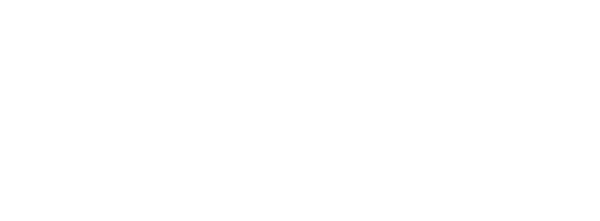

With the certified flight instructor on board, the Beechcraft departed from the Warrenton, Virginia Airport at 1545. The aircraft headed south, and climbed to 3000 feet ASL. No en route air traffic services were requested by the pilots of the Beechcraft, nor were they required to do so in the airspace in which they were operating. The recorded radar data indicated that the Beechcraft was transmitting on transponder code 1200.

At 1555, the now northbound Beechcraft was 13 nm south of the Culpeper Regional Airport at 3000 feet ASL. At this time, the Piper PA-28-140 departed the Culpeper Airport under VFR and was climbing eastward. At 1600, the Beechcraft started a descent. As the Beechcraft descended, their converging point of approach was 600 feet vertical and 0.9 nm lateral.

It is not known if either pilot saw the other aircraft, or if the 2 aircraft were on the same radio frequency.

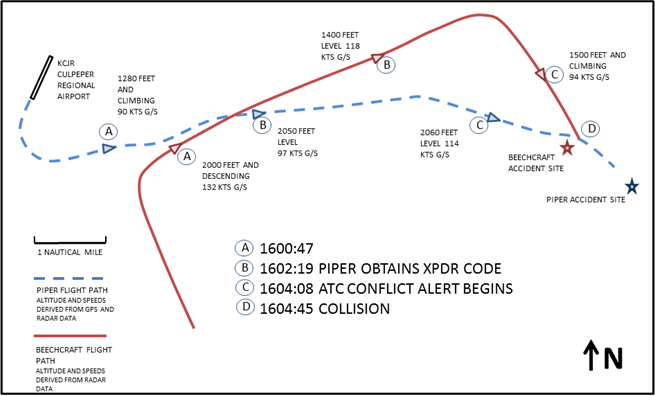

The Piper and the Beechcraft collided on a 45° convergent path from the Piper’s left side. Field-of-view analysis showed that there was a high likelihood that each aircraft was visible to the other, meaning that no aircraft structure would have obscured the view of either approaching aircraft. The Beechcraft pilot’s view may have been obscured by the instructor’s head, depending on each pilot’s seat position and posture, but the instructor’s view would have been unobstructed. There were no indications that either aircraft maneuvered to avoid the other.

As the 2 aircraft collided, the Piper’s propeller severed the Beechcraft’s fuselage just aft of the pilots’ seats. Without the empennage and ruddervators attached, the Beechcraft’s cockpit and wings entered a dive, resulting in an impact that was not survivable and a post-impact fire. The right ruddervator and aft portion of the empennage/tail cone of the Beechcraft remained embedded in the Piper’s fuselage. The Piper’s engine failed, and there was a loss of airspeed indication. The pilot then completed a successful forced landing into a pasture.

Good visual meteorological conditions were reported in the Warrenton area.

Neither aircraft was equipped, nor was required by regulation to be equipped, with any form of aircraft collision avoidance technology.

Both aircraft were visible on radar at the Potomac TRACON ATC facility. The controller on duty received a system automated collision alert but assessed the risk of a collision between the two aircraft as insignificant. The controller was also distracted at the time by providing separation between IFR aircraft in the sector. No alert was raised by the control and no conflict information was given to the two occurrence aircraft.

The only preventative measure which was left to these two pilots was the VFR method known as “See and Avoid”. Neither pilot saw the other aircraft in time to avert a mid-air collision, likely due to the inherent limitations of the “See and Avoid” principle. This principle is only effective if both pilots maintain a constant lookout for conflicting traffic.

Cessna A185E Seaplane - Fuel Starvation/Loss of Control/Water Impact

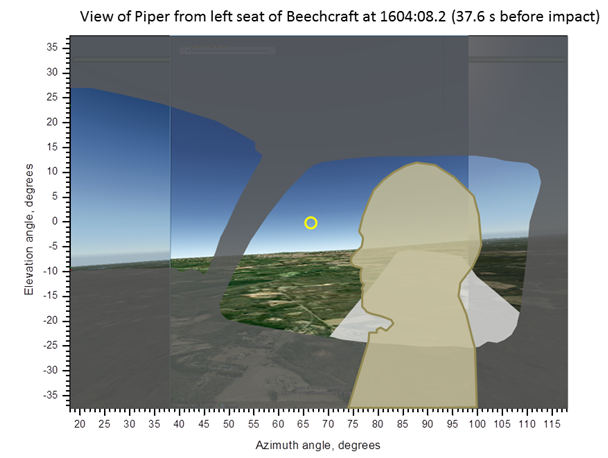

At approximately 1448 the Cessna A185E floatplane left the La Tuque, Quebec, seaplane base for a 20-minute sightseeing flight. The aircraft took off towards the north and climbed to an altitude of 1600 feet above sea level. After approximately 12 minutes of flight time, the engine failed. The pilot decided to proceed with water landing in the Bostonnais River.

During the descent, the pilot attempted to restart the engine, but without success. The pilot executed a steep left turn in order to avoid terrain but the aircraft lacked sufficient airspeed for the successful completion of the turn. The aircraft’s wing stalled and the pilot did not have sufficient altitude or thrust to recover from the stall. The aircraft struck the surface of the water in a nose down attitude and came to rest inverted in the water. Local residents reacted quickly, contacting emergency services and offering assistance.

The aircraft was occupied by the pilot and 4 passengers. One passenger was fatally injured as a result of this accident.

The pilot held the necessary licence and qualifications for the flight, in accordance with existing regulations. The pilot had accumulated 550 flight hours, approximately 400 of which were in a Cessna 185 floatplane. There was no indication that fatigue contributed to this occurrence.

The occurrence flight was the third flight of the day. The first flight was of short duration to a nearby lake. Prior to the second flight the pilot used a dip-stick to measure the amount of fuel remaining and determined that here was approximately 15 gallons per side for the second flight. The second flight occurred without incident and was approximately 20 minutes in duration.

Prior to the third and final flight, the pilot did not check the fuel level and estimated that there was approximately 10 gallons in the left tank and 15 gallons in the right tank.

The pilot took off with the fuel selector in the “BOTH” position but once airborne, switched to the left tank. Approximately 12 minutes after takeoff and at an altitude of 1600 feet ASL, the engine stopped producing power due to fuel starvation.

Owners and operators of Cessna 185 aircraft are aware that the fuel indicators lack precision, particularly when a tank’s fuel quantity is below the one-quarter mark. For this reason, the majority of owners of Cessna 185 aircraft of similar type have turned to using dipsticks to measure fuel quantities.

Searches in various aviation accident databases show that many occurrences, particularly those involving general aviation, point to poor fuel management as a contributing factor to in-flight fuel starvation accidents.

TSB investigators discovered that due to the pilot’s failure to positively check the fuel quantity prior to the occurrence flight, there was no way to predict the precise moment at which the left tank would become void of fuel causing loss of power from the engine.

Cessna 172M - Loss of Control and Collision with Terrain

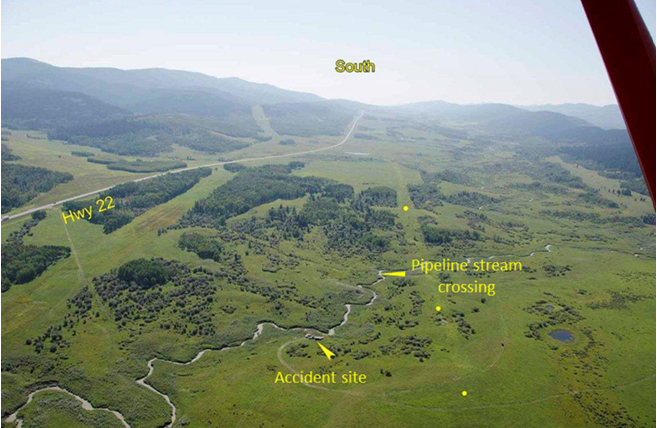

The Cessna 172M departed Springbank Airport, Alberta, on a visual flight rules flight to conduct a pipeline patrol. While the aircraft was circling an area of interest on the pipeline it entered a spin, descended steeply, and collided with terrain at 1734 Mountain Daylight Time. The pilot, who was the sole occupant of the aircraft, sustained fatal injuries. The aircraft was destroyed by impact forces, and there was no post-impact fire. The 406-MHz emergency locator transmitter activated on impact.

Witness statements indicated that, in the vicinity of the accident site, the aircraft made several low-level left-hand turns. A change in engine sound was heard, accompanied by entry into a spin to the left and a rapid descent. When the aircraft did not recover from the descent, an emergency call was made via satellite phone by witnesses, who reached the site on foot approximately 1 hour after the accident.

Records indicated that the pilot was certified and qualified for the flight in accordance with existing regulations. The pilot had a total flying time of approximately 6900 hours. The pilot was reported to be well rested and in good spirits on the day of the accident.

Weather conditions for this flight were very favorable. Temperature was 19°C, the dewpoint was 6°C, and the wind was at 5 knots, gusting to 12 knots, visibility was unlimited and the sky was clear.

Records indicated that the aircraft was certified, equipped, and maintained in accordance with existing regulations and approved procedures. Wreckage examination did not reveal any pre impact discontinuity in the flight controls.

At the time of the accident, the weight and balance of the aircraft was determined to be within limits.

The pilot was maneuvering at relatively steep angles of bank, at low airspeeds and at a low altitude. The pilot was also taking photographs of the subject area while maneuvering the aircraft.

Flight conditions during the final moments of the flight were conducive to stall and subsequent spin entry. These conditions would have been a relatively low airspeed/high angle of attack, steep bank angle to the left, moderate engine power, and possible excessive left rudder application. The steep descent, short wreckage trail, and low ground speed point to a loss of control at low altitude due to aerodynamic stall. Ground scars indicated that the spin rotation had been stopped; however, insufficient height remained to arrest the high rate of descent.

Comments from TSB investigators include:

- For undetermined reasons, while maneuvering at low level control was lost and the aircraft entered an aerodynamic stall and spin.

- Although the pilot was able to arrest the spin, the low altitude of the aircraft prevented recovery from the stall before the aircraft struck the ground.

- The conduct of single pilot, low level flights that include additional tasks beyond flying the aircraft, such as photography, increases the risk of loss of control.

Piper PA-28R and Lake Buccaneer LA-4-22 - Mid Air Collision

The privately-registered Piper PA-28R-200 Arrow was approaching St. Brieux, Saskatchewan, on a flight from Nanton, Alberta, with the pilot and 2 passengers on board. A privately-registered Lake LA-4-200 Buccaneer amphibian was en route from Regina to La Ronge, Saskatchewan, with the pilot and 1 passenger on board. At approximately 0841 Central Standard Time, the 2 aircraft collided about 8 nautical miles (nm) west of St. Brieux and fell to the ground at 2 main sites about 0.5 nm apart. Both aircraft, which were being operated in accordance with visual flight rules, were destroyed and there were no survivors. There was no post-crash fire and the emergency locator transmitters did not activate.

The pilot of Piper aircraft held a private pilot licence with a valid Category 3 Medical Certificate, which required that the pilot wear glasses when flying. The pilot had accumulated approximately 1000 total flight hours on the PA-28 type aircraft. Records indicate that the pilot of the Piper was qualified for the flight in accordance with existing regulations.

The pilot of Lake Buccaneer held a private pilot licence with a valid Category 3 Medical Certificate, which required that he wear glasses when flying. He had recently obtained his licence and had accumulated just over 100 total flight hours, with approximately 24 flight hours on the Lake LA 4 200 type aircraft. Records indicate that the pilot of the Lake Buccaneer was qualified for the flight in accordance with existing regulations.

Weather at the time of the accident was considered good VFR and was therefore not considered a factor in this occurrence. Both aircraft were properly registered and maintained in accordance with federal Aviation regulation and the aircraft were both operating within their respective operational and performance envelopes.

The TSB investigation reveals that the 2 aircraft were following intersecting tracks. Consequently, there was a risk that they could arrive at the same point in space at the same time.

The relative position of each of the occurrence aircraft just before the collision would have made visual acquisition difficult. The Piper aircraft was descending from a higher altitude than that of the Lake Buccaneer. As a result, the Piper may have been obscured by the left wing of the Buccaneer. Likewise, the Buccaneer may have been obscured from the Piper pilot's view by the nose of the aircraft.

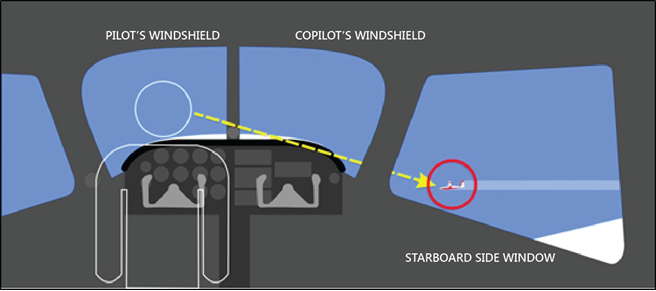

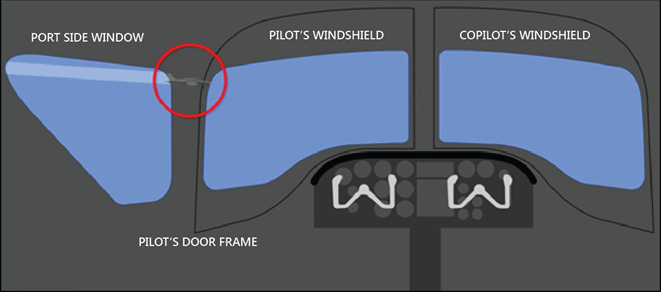

The diagrams below indicate the positions of the aircraft relative to each other and the aircraft flight decks

View from the left seat of the Pipe aircraft which is partially obstructed by the nose of the aircraft.

View from the left seat of the Lake Buccaneers which is partially obstructed by the aircraft structure.

Relative position of both aircraft at the moment of impact.

The TSB investigation concluded that:

- Both aircraft arrived at the same point and altitude at the same time, which resulted in a mid-air collision.

- The converging position of the 2 aircraft relative to each other, coupled with physiological vision limitations, likely rendered visual detection extremely difficult. As a result, the available reaction time was reduced to a point where collision avoidance was not possible.

- The left ailerons and part of the wings from both aircraft were shorn off in mid-air during the collision. This would have rendered both aircraft uncontrollable, and would have precluded either aircraft from recovering after the collision.

- Aircraft operating in visual flight rules conditions are at continued risk of collision when the “See and Avoid” principle is relied upon as the sole means of collision avoidance. Research has shown that it takes approximately 12.5 seconds for a pilot to take evasive action upon recognition of an impending collision. In addition to reaction time, distance is another critical factor which affects a pilot's ability to see and avoid a collision. This is especially true for aircraft beyond 2 nm.