Investigation Reports

Cirrus SR-22: Loss of Control and Collision with Terrain

A Cirrus SR-22 took off for a "Round-Robin" VFR slight near Calgary Alberta. After a touch-and-go at its initial destination, the aircraft began its return flight. But while en route, the aircraft stalled, spun, then entered a spiral dive and impacted the ground, killing all three occupants. The wreckage was then consumed by a post-crash fire.

Due to the near-vertical attitude, all wreckage was located with 60' of the point of impact. The severe post-crash fire consumed all but the tail, so there was very little information to be gleaned from flight instruments, etc. As a result, airframe failure or system malfunctions couldn't be ruled out conclusively. However, investigators were able to deduce that the engine had been running all the way to the ground and that both door latches were in the closed position on impact.

Weather was ruled out as a contributing factor as the conditions were C.A.V.U., with nothing more than a light breeze at the time of the crash. The pilot-in-command had a valid private pilot license in addition to instrument, multi-engine & night ratings. His total flight time was 567 hours of which 448 were in a Cirrus. The pilot had also taken a transition course in the SR-22, in addition to 50 hours of dual on his new aircraft and another 150 hours with an instructor to improve his skills and remain current. Not surprisingly, the pilot was described as "...competent and cautious in his approach to flying." The other two passengers on board were also pilots, and both had just become partners in the aircraft that day. The flight was more than likely intended to familiarize both new owners with their airplane.

Due to the all-consuming nature of the post-crash fire, investigators had to piece together the causes of the crash from other sources. One clue was an "oscillation" reported by witnesses after the aircraft's touch-and-go landing. As the Cirrus employs a unique control system consisting of a single yoke handle protruding from the left and right sides of the instrument panel, and as roll inputs are controlled by rotating the handle, there is a short adjustment period for pilots used to more conventional systems.

And as this was the first flight for both new owners, it is reasonable to assume that the right seat "passenger" may have been flying the plane when the incident occurred. (The post-landing "oscillation" is another indication that this may have been the case.) If this is what happened, it is again feasible that the stall and ensuing spin were caused by the inexperienced right-seat passenger over-correcting the distinctive Cirrus controls.

The saddest part of this tragedy is that the Cirrus was equipped with a rocket-powered Airframe Parachute System. And as the Cirrus "...is not approved for spins and has not been tested or certified for spin recovery characteristics, the only approved and demonstrated method of spin recovery is activation of the Cirrus Airframe Parachute System. Because of this, if the aircraft departs controlled flight, the CAPS must be deployed."

The aircraft appears to have entered its spin about 1,600' above ground, which was more than sufficient for the CAPS to have been deployed. However, the pilot opted not to fire the parachute system and appears to have attempted a normal spin recovery, which degenerated into a spiral dive. There were some indications that a recovery had been successfully achieved, however during the attempt at a pull-out, the aircraft struck the ground at high speed.

What lessons can be learned from this tragedy? We may all have been tempted to let our right-seat passengers "try the controls" from time to time, but in this case that decision – if made – may have led directly to the subsequent crash.

As for the decision not to use the ballistic parachute ... while probably made thinking the procedure might damage the aircraft in some manner, whomever was at the controls forgot that the Airframe Parachute System is the only approved manner for recovering from spins in a Cirrus.

The tragic end to this flight only serves to prove the truth of this critical part of the Cirrus Aircraft's certification.

Investigation Reports

Vans RV-7A: In-flight Separation and Impact with Terrain

The amateur-built Vans RV-7A was part of a formation of 3 aircraft that departed Lindsay, Ontario, on a VFR flight to Smiths Falls, Ontario. En route, 1 of the 3 aircraft diverted to Bancroft, Ontario. The 2 remaining aircraft continued with the RV-7A in tandem. The lead conducted a series of aerobatic manoeuvres, which the RV-7A Pilot was to film. While manoeuvring, the lead lost contact with the RV-7A, conducted a visual search, but could not locate the aircraft. The Joint Rescue Coordination Center was alerted and a search was conducted. The aircraft was located in a wooded area, but was destroyed on impact - and the pilot, the sole occupant, was fatally injured.

The aircraft struck the ground in a near-vertical attitude, flipped over and came to rest upside down. The Emergency Locator Transmitter functioned, but its range was reduced significantly, as the antenna was sheared on impact. There was no post-impact fire, however the instrument panel was destroyed along with most of the instruments. But ... the GPS, EFIS and a video recorder (being used to record the lead aircraft's aerobatics) were all salvaged from the wreckage.

In addition, the basic cause of the crash soon became quite evident; the vertical stabilizer and top half of the rudder were both missing (though eventually located just over half a nautical mile away).

It was evident that the aircraft had broken up in flight, and the reason for this was relatively simple to deduce as the entire incident had been video-taped by the onboard recorder.

When the visual evidence was correlated with information from the EFIS & GPS, it soon became apparent that the rudder and vertical stabilizer had both separated from the aircraft as a result of flutter at excessive airspeeds. The RV-7A has a maximum manoeuvring speed of 124 knots and a Vne of 200 knots, but the recording devices showed that the accident aircraft hit speeds of 234 knots, which inevitably triggered the flutter and in-flight separation of the vertical tail surfaces.

A contributing factor may have been the elaborate paint scheme which could have put the aircraft over gross, moved the C of G rearward, and added weight to the rudder (decreasing its "flutter speed" by 50 knots or greater!) Once the vertical surfaces departed the airframe, the aircraft became uncontrollable, rolled inverted and dived straight in.

Cessna 150G / 150L Mid Air Collision

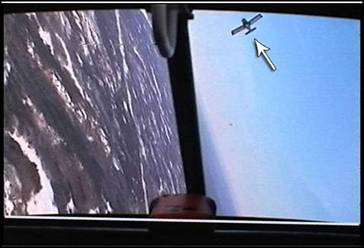

At about 1600 Pacific Standard Time in daylight conditions, a group of 4 light aircraft took off from the Langley Regional Airport in Langley, British Columbia, for a local formation flight to Chilliwack, British Columbia. At about 1615, during a turn, one of the Cessna 150 and another Cessna 150 collided. The 2 aircraft briefly descended joined together and out of control, but at about 400 feet above ground level, they separated. The first C150 broke up in flight and fell to the ground; the 2 occupants were fatally injured and the aircraft was destroyed. The pilot of the second C150 regained control of the aircraft and landed in a farm field without injury. There was no fire and the emergency locator transmitter on the first C150 activated upon impact with the ground.

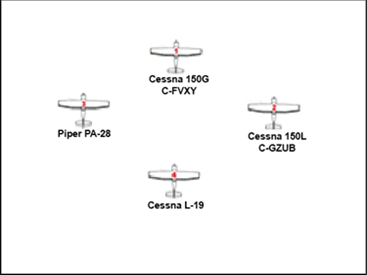

Three of the pilots in the group were familiar with formation flying because they had flown together many times at various fly-past events and had practiced over the Lower Mainland of British Columbia. As a newcomer to the group, the pilot of the Cessna 150 at the right side of the diamond formation, having previously accompanied other pilots during two formation flights, was flying as the pilot of his own aircraft in the formation. The lead aircraft was the first Cessna 150 (in the lead of the diamond formation) had one passenger on board. On the left side of the diamond formation was a Piper PA 28 aircraft and at the rear of the formation was a Cessna L-19.

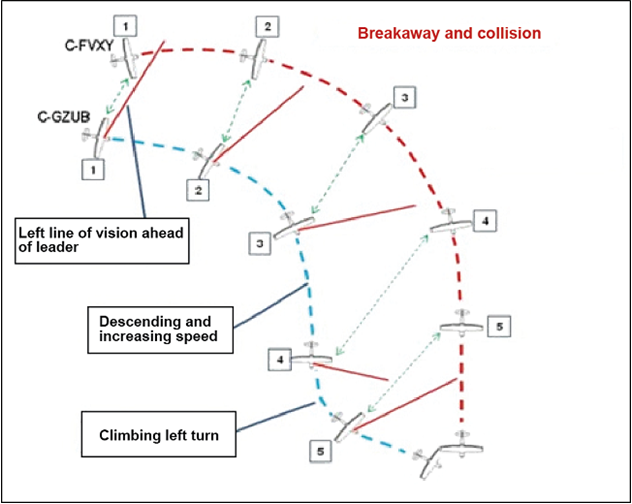

During left hand formation turn maneuver, the lateral distance and step-back of the number 2 aircraft on the leader's right side increased somewhat, but the right hand C150 returned to its original position once the flight rolled out on the northerly heading.

Shortly after, the leader announced a right turn and this time advised the number 2 aircraft to reduce engine power since it was on the inside of the turn. The 4 aircraft then entered a level, 15°angle-of-bank right turn at 1500 feet asl to return to the southerly heading.

During the turn, the pilot of the right diamond lost sight of the lead aircraft, turned away to the right and descended. After a brief interval, the right side diamond turned left and climbed while the pilot searched for the leader to rejoin the formation above.

At 1615, seconds after the leader called a roll-out, the two aircraft collided at almost 70° to each other. The aircraft began to rotate and descend joined together, and fell out of control for several seconds. At about 400 feet agl, the aircraft separated; the lead diamond aircraft broke up in flight and fell to the ground, while the pilot of right side diamond regained control and landed the aircraft without engine power in a farm field.

No reports of turbulence or other unfavorable weather phenomena were observed. Weather was not a contributing factor in this accident.

There was no indication that the performance of the pilot who died in the accident was degraded by physiological factors or incapacitation. A review of both pilots' recent activities found no indication that fatigue or other human factors contributed to the accident circumstances.

This accident was an associated midair collision: the pilots involved were intentionally flying in close proximity in a pre-arranged formation flight. The flight profiles of both accident aircraft indicate that neither pilot saw the other aircraft in sufficient time to initiate effective and timely evasive action. The investigation could not determine what was taking place in the flight deck of the lead at the time of the occurrence.

No evidence of pre-existing mechanical defect in either aircraft was found. Accordingly, this analysis focuses on the operational issues and hazards of formation flight, and on the flight path, to provide the most likely explanation as to why these 2 aircraft collided.

- During the right-hand turn in formation flight, the pilot of right side diamond lost sight of the lead aircraft.

- After initially adopting a flight path that effectively eliminated the risk of collision, the pilot of the right side diamond turned back toward the leader so as to rejoin the formation, thereby unintentionally placing the aircraft on a course leading to their collision.

- The high-wing configuration of C150 significantly restricted the field of vision, and, during the left-hand turn, the pilot was unable to see the lead aircraft on a collision course.

- The impact damage resulting from the in-flight collision rendered the lead aircraft uncontrollable, and the aircraft was unable to maintain flight; it descended rapidly and collided with the terrain.

- During its pre-flight briefing, the group had not discussed the contingency procedures for loss-of-sight of an aircraft, and it did not review the accepted practices for returning to the formation.

- For the occupants of lead aircraft, the forces of the in-flight impact and the collision with the terrain exceeded normal human tolerance, and the accident was not survivable.

- Formation flying involving high-wing aircraft poses elevated risk due to the limited cockpit vision angles.

- Formation flying involving aircraft of dissimilar aircraft types is challenging and demands higher skill levels, particularly when combining high-wing and low-wing aircraft. This aircraft combination creates an even greater risk for casual formation flyers.

- Formation flying demands higher levels of skill, discipline, and training than conventional flying. Without appropriate formal training to achieve those increased levels, the risk of in-flight collision is elevated.

Cessna 185E Controlled Flight into Terrain

A Cessna 185 was on a night visual flight rules flight from Peace River Airport, Alberta, to Fort St. John Airport, British Columbia. At approximately 1817 Mountain Standard Time, the aircraft struck the ground 12 nautical miles east of the Fort St. John Airport. The pilot, and sole occupant, of the aircraft sustained fatal injuries. The aircraft was destroyed by impact forces and there was no post–impact fire. The 406 MHz emergency locator transmitter activated on impact.

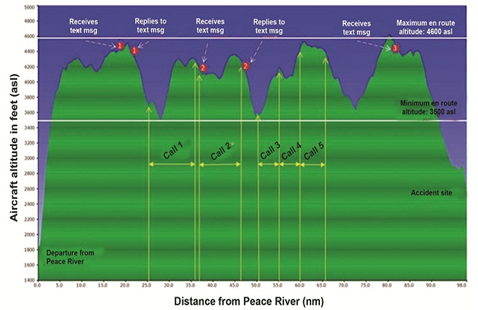

The pilot then departed at 1706, reporting westbound at 4500 feet above sea level (asl). Between 1719 and 1755, the pilot engaged in 2 text message exchanges and conducted 5 voice cell phone communications totaling 28 minutes. The pilot received a final text message at 1806, 11 minutes before the aircraft impacted the ground.

At 1809, 23 nm east of the Fort St. John Airport, the aircraft began a gradual descent of approximately 170 feet per minute, with a ground speed of 90 knots. (Ground elevation was approximately 2400 feet asl at the accident site.) The aircraft was 18 nm east at 3200 feet asl at 1813 when the pilot was in contact with the Fort St. John Flight Service Station (FSS). The pilot was given all appropriate aerodrome information for approach and landing. There were no further communications with the FSS.

From 1815 to 1816, the pilot momentarily leveled off at 2900 feet asl, 15 nm east of the airport, before resuming the descent. The descent continued uninterrupted until the last radar contact at 1817, 12 nm from the airport at 2400 feet asl.

The aircraft contacted the tree tops at approximately 75 feet agl. The middle of the left wing strut was struck from below and slightly forward. This caused the strut to buckle upward, resulting in the strut’s wing and fuselage fittings to fail due to the overload force exerted upon them. With the strut detached, the left wing lifted up and broke free of the fuselage at the wing attachment fittings. The left wing and strut were found approximately 209 feet from where the left wing had struck the trees.

After the left wing had separated from the aircraft, it rolled to the left and continued to descend, impacting the ground on its left side 370 feet from where the left wing was found. The aircraft bounced a further 40 feet before coming to rest on its back.

The cockpit instruments were largely destroyed as a result of the impact. The tachometer face was recovered indicating a power setting of 2400 rpm. The altimeter was not recovered; therefore, it could not be determined if it was set to the Fort St. John Airport altimeter setting.

There had been no outstanding mechanical defects had been reported concerning the aircraft and it was being operated within the applicable weight and balance limitations for the flight. Conditions at the time of the occurrence were conducive for night visual flight rules (VFR) flight. Approximately 34% of the moon’s face was visible.

The gradual rate of descent, constant ground speed and flight path would also suggest that the aircraft was under the control of the pilot. The aircraft had experienced several large altitude deviations while the pilot was using his cellphone. While it did not appear that the pilot was actively engaged in cell phone communications during the last 11 minutes of the flight, this distraction was prevalent throughout the flight and in conjunction with the night conditions encountered, may have contributed to the CFIT event.

The findings from the TSB include:

- For undetermined reasons, the pilot descended too low or was not aware of the descent and low altitude of the aircraft, which resulted in an impact with terrain.

- Pilots who engage in non–essential text and voice cell phone communications while conducting flight operations may be distracted from flying the aircraft, placing crew and passengers at risk.